Why Humans Create Art?

A personal investigation about what I think about when I think about Art.

I have been thinking about my relationship with Art a lot. I am sure other humans do the same. It is a funny word right?

A-R-T

Wonder if it came from the word heart?

H-E-A-R-T

or from the word tart?

T-A-R-T

or form the word depart?

D-E-P-A-R-T

These words carry function, scent and meaning. Hmm. Okay enough of this stream of consciousness thinking. There were some questions that recently made me reflect on my relationship with Art and got me thinking about how it has changed over time. These questions included,

Where did the word Art actually emerge from? What is the history of Art? What constitutes Art? How has my relationship to Art changed over time? What is good Art? Who decides what is good Art? What are some frameworks or lenses that help me appreciate Art? How do I feel when I engage with Art? How do I access Art? Where can you see Art?

What do I want from Art?

I will explore my answers to some these questions in this essay. In the process I hope to find some clues to why humans create art.

Disclaimer: This is a very personal essay

This is my understanding of the word and what it means to me. I think I would like to have this conversation and ask these questions to every person I meet in the world. We have 7 billion people and more on this planet! That is a lot of conversations to have. But this essay is a good start in that direction. For Art can mean different things to different people at different points in their lives. Very often the first questions I want to ask new people I meet are the following,

What Art do you Love? Why did it mean so much to you at that point in your life? What did you notice in that piece of Art? How has your relationship to that piece of Art changed over time? Do you still love Art?

Where did the word Art actually emerge from?

The term “Art” traces its roots to the Latin word ars which denotes “skill,” “craft” or “technique.” In ancient years, ars was used more liberally to include any learned skill like carpentry, rhetoric, even medicine, which is not restricted to what contemporary society regards as “fine art.” The Latin ars is related to the Greek word techne which also means “skill” or “craft” and is the root of modern terms like “technology.” Much later, and particularly in post Renaissance Europe, “Art” as a term started shifting more towards the creative and expressive activities of painting, sculpting, composing or writing, and distinctively set apart from more functional or utilitarian works of craftsmanship.

I then asked ChatGPT to help me understand how the word for "Art" varies across cultures and reflects the diverse understandings of creativity and expression. Here is the response it produced:

In French, it is art, pronounced similarly to English but with a softer ‘r’, and used broadly for fine arts and crafts. Spanish and Italian both use arte, rooted in Latin ars, and encompassing visual, performing, and literary arts. In German, the word is Kunst, derived from the verb können (to be able), highlighting skill and craftsmanship. Russian uses искусство (iskusstvo), which also stems from the idea of mastery and human ingenuity. In Arabic, فن (fann) conveys a wide array of artistic activities and aesthetics, often tied to beauty and expression. In Mandarin Chinese, 艺术 (yìshù) combines characters meaning "skill" and "technique," emphasizing both creativity and discipline. Japanese uses 芸術 (geijutsu), where gei refers to performance or technique and jutsu to art or skill, suggesting refinement and tradition. In Hindi, कला (kala) denotes both fine arts and traditional crafts, deeply connected to cultural heritage. Finally, Swahili uses sanaa, a term that spans music, dance, painting, and storytelling, often rooted in communal and cultural expression. Together, these terms illustrate how the concept of art, while universal, is shaped by the values and histories of each language and society.

So, the modern idea of "Art" as self-expression or aesthetic creation is relatively recent, evolving over centuries from a broader concept of skilled human activity.

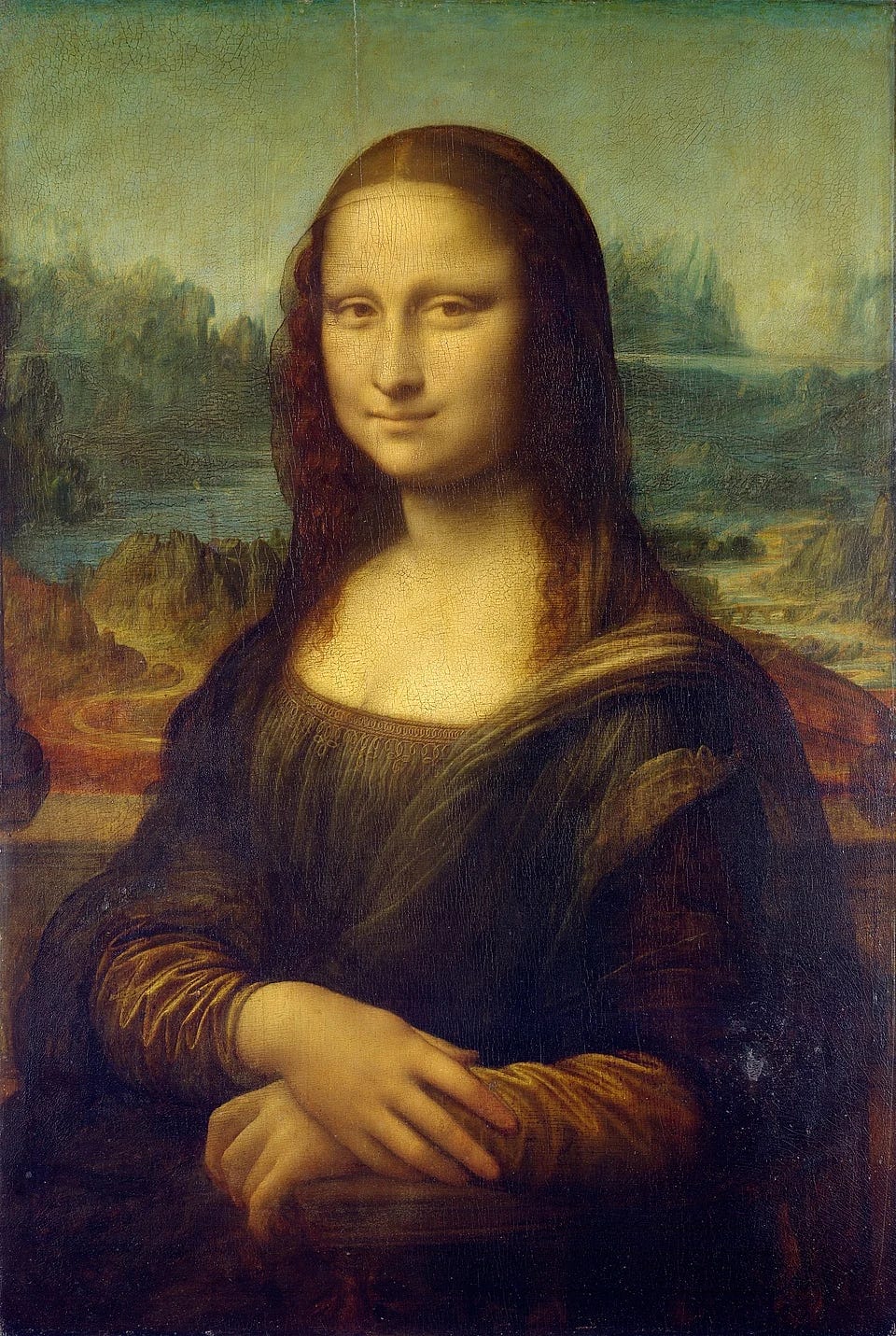

Now I want to know how Art has evolved over time from a historical lens. But before that here are some snaps of Art I love with a short quotation of why it brought me joy and stayed with me over time. I would be really happy if you left me an Art recommendation and a reason it moved something in you in the comments.

#1 Art I love - Reflections on the Thames by John Atkinson Grimshaw (1880)

For no one painted the moonlight and captured its beauty like Grimshaw for me. Explore his other artworks here.

#2 Art I love - Nighthawks by Edward Hopper (1942)

For no one captured the loneliness of urban living and the emotions left unsaid on our faces like Hopper did for me. Explore his other artworks here.

#3 Art I love - The Diaries of Frida Kahlo

For Kahlo changed my relationship to journaling and helped me bring sketching, colours and random musings to this very personal practice. Explore her other artworks here.

#4 Art I love - Sit by Vikram Seth (1990)

For he was the first poet that spoke to my heart and I read this poem when I just turned 26. Explore his poems here.

#5 Art I love - The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh (1889)

For he changed my relationship to colours by adding emotions to them in my mind. Blue was never the same after I saw this painting in person at The MoMA in New York in 2019. Explore his other paintings here.

A Short History of Art

I am no art historian. So I needed some help and turned to ChatGPT to help me understand and summarize art history in an accessible and easy manner. I have paraphrased its response with links to the original artworks in this part of the essay. I have also added my own notes about how the purpose of art has changed and evolved over time.

Art history is a global story that begins with early expressions of human creativity. In Southern Africa, the Blombos Cave engravings (c. 75,000 BCE), the Bhimbetka rock shelters in India (c. 30,000 BCE), the Apollo 11 cave stones in Namibia (c. 25,000 BCE) and the Lascaux cave paintings in France (c. 17,000 BCE) are some of the oldest known artworks. In South America, the Nazca Lines in Peru (c. 500 BCE–500 CE) and intricate Moche ceramics (c. 100–800 CE) demonstrate rich visual traditions. Meanwhile, Indigenous civilizations like the Maya and Inca developed monumental art and architecture such as pyramids, murals, and goldwork. In Asia, Buddhist sculpture in Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan) and Hindu temple carvings in India (e.g. Khajuraho, 10th century) flourished, paralleled by Chinese ink painting and Japanese ukiyo-e prints.

Art served as a means of recording history documenting important events since pre historic times.

In Mesopotamia: The Stele of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BCE) combines visual and written art to record one of the earliest legal codes, showing Hammurabi receiving laws from the sun god Shamash linking divine authority to state governance. In India the Ashokan Pillars (3rd century BCE) are inscribed with edicts from Emperor Ashoka, spreading messages of moral governance and Buddhist values across the Mauryan Empire. In the Mayan Civilization: Stelae (stone monuments) in cities like Tikal and Copán recorded the reigns of kings, important battles, and religious ceremonies through detailed carvings and hieroglyphs. In China the Terracotta Army (c. 210 BCE) in the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China, reflects his power and ambition to rule in the afterlife, commemorating his unification of China.

Art was used to express spirituality and power by ancient civilizations across the world.

In ancient Egypt, art was a key tool for expressing power, often serving both religious and political purposes. Pharaohs were depicted as larger-than-life figures in monumental statues. The Temple of Abu Simbel features colossal statues of Ramses II and carvings depicting his military victory at the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE), portraying him as a mighty and divinely sanctioned leader. In ancient India, art was used to assert royal power and spiritual dominance, especially in Hindu and Buddhist temples. Kings commissioned elaborate sculptures of gods and themselves, such as those seen in the temples of Khajuraho, where the divine and the royal were intricately intertwined. Temples like those at Ellora featured elaborate carvings of deities to reflect cosmic order and divine presence. These works weren’t just decorative—they were tools to communicate sacred truths and legitimize rule.The Maya carved intricate glyphs and built temples like those at Tikal to connect with celestial cycles. In West Africa, the Benin bronzes depicted kings (obas) in regal forms to reinforce royal authority.

Art has long been shaped by economics. Wealthy patrons, empires, and markets often fund and influence its creation.

The Global Renaissance (c. 1300 CE –1600 CE) saw not only Michelangelo and da Vinci in Europe, but also intricate Mughal miniatures in India and Benin bronze plaques in West Africa. However during the Renaissance, wealthy families like the Medicis in Florence sponsored artists such as Michelangelo and Botticelli to enhance their status and legacy. In Mughal India, emperors commissioned lavish miniature paintings to display imperial grandeur. The Dutch Golden Age saw a booming art market driven by a rising merchant class, leading to works by artists like Vermeer and Rembrandt. Even today, global art fairs and collectors influence what styles and artists gain recognition. Economics doesn't just fund art but it helps shape what gets seen and remembered. The 17th to 19th centuries brought Baroque and Romanticism in the West, alongside Qing dynasty painting in China and Casta paintings in colonial Latin America.

Art can raise awareness, spark empathy, and give voice to marginalized communities.

It creates spaces for dialogue, healing, and collective action in times of injustice or crisis.

From murals to music, art can inspire social change by making complex issues feel personal and urgent.

In the 20th century (c. 1900 - 2000), modernist movements reshaped art worldwide: Picasso’s Cubism (1907), Mexican muralism (Diego Rivera, 1920s), and the Négritude-inspired work of Senegalese artist Papa Ibra Tall (1950s). Postcolonial and contemporary artists like Frida Kahlo (Mexico), Esther Mahlangu’s Ndebele (South Africa), El Anatsui (Ghana), Ibrahim El-Salahi (Sudan), Wangechi Mutu (Kenya), Tarsila do Amaral (Brazil) and Ai Weiwei (China) have challenged dominant narratives, blending local traditions with global concerns. Picasso’s Guernica (1937) exposed the horrors of war, while Keith Haring’s vibrant activism during the AIDS crisis combatted stigma through public art. Contemporary artists like Ai Weiwei use installations to protest oppression, and the Black Lives Matter murals painted globally after George Floyd’s murder became symbols of solidarity and demands for justice. Similarly, Theaster Gates transforms abandoned buildings into cultural hubs, revitalizing neglected communities. Even with all these positive signs art does have its limitations and cannot solve all human problems. But it can be a powerful tool to point us in the right direction.

Art’s impact can be limited by accessibility, as not everyone has the means or opportunity to engage with it. Its messages may also be misinterpreted or diluted, reducing its effectiveness as a tool for change. Additionally, art alone cannot solve systemic issues and it often requires accompanying action, policy, or education to create lasting transformation.

What constitutes Art?

Art is any human-made expression that uses creativity to communicate ideas, emotions, or experiences. It can take many forms including,

drawing

painting

print making

collage

textiles

sculpture

music

dance

photographs

ceramics and pottery

architecture

performance art

literature (poetry, prose, plays)

film (feature films, short films, documentaries)

digital photography & illustration

digital painting & illustration

graphic design

animation

augmented reality (AR) & virtual reality (VR)

AI-generated art

Honestly it has too many forms. And one list is not sufficient to answer this question. You can break down each category listed above and create many more such lists that go on forever. Now that is for another time.

I now want to explore how my relationship to art has changed over time. But before that here are some more snaps of Art I love with a short quotation of why it brought me joy and stayed with me over time. I would be really happy if you left me an Art recommendation and a reason it moved something in you in the comments.

#6 Art I love - Jhol by Mannu, Annural Khalid and Coke Studio Pakistan (2024)

For how it captured emotions in a song and how it showed longing through its lyrics. Maybe my favourite song of 2025 and for some reason I have new songs I love every few days, weeks, months or years. Explore other music by Maanu and music by Annural Khalid at these links.

#7 Art I love - Cleopatra by the Lumineers (2016)

For how it told a story through a music album and how it allowed contradictory emotions to co exist and flourish in the same narrative. I can safely say that this is my favourite music album and it has remained that way for a long time. Explore other music by The Lumineers here.

#8 Art I love - The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri (2003)

For how it helped me make sense of my experience as an immigrant and the many journeys and hurdles that my ancestors had to travel to give me the life I have today. It was also one of the very first novels I read and loved dearly. Explore other books by Jhumpha Lahiri here.

#9 Art I love - Interstellar by Christopher Nolan (2014)

For how it helped me understand how insignificant I am on a inter planetary scale. Also made me appreciate the many technical aspects of bringing a movie to life. Explore other movies by Christopher Nolan here.

#10 Art I love - Superboys of Malegaon by Reema Kagti (2024)

For helping me realize that at the end of the day one of the most important reasons we create art is to provide comfort, warmth, hope and love to each other in the good and bad times. This was a recent favourite. Explore other movies by Reema Kagti here.

A Personal History of My Relationship with Art

My relationship with Art has changed significantly over time. Here is a rough timeline of the same.

Age of 12 - I hate reading. I hate drawing. I love Bollywood movies. I don’t know what music I like.

Age of 15 - I love music and love the movies. I watch a lot of popular films from all over the world. I also start listening to the music my friends love listening too.

Age of 18 - I love reading. I had an English Teacher in high school that helped me develop this passion. I wasted so much time. I have to try read every book in the world now. I pursued an Arts Degree and spent three years reading everything I could get my hand on in the Sciences and Social Sciences.

Age of 21 - All writing and art is biased or political. I have to choose my books and art carefully.

Age of 25 - I find joy in painting, dance, drawing and digital media. I understand that there are many ways to be an artist beyond literature, music and films.

Age of 30 - I slowly come to realize that art is one tool among many that humans have created to understand and make sense of the world around them. Art that is meaningful to me will be disliked by someone I love. That is okay. Enjoy it anyways! Can I explore becoming an artist myself? Can I create something artistic that is of some value to other humans. Hmm. This will take some more time. I still have some self doubt.

How does Art make me feel? or the Book that changed my relationship with Art

But in 2016, in my second year at university I came across an old tattered copy of a book in a back corner of the collections of the Asiatic Society Library in Mumbai.

It was titled, Nāṭya Shāstra and was written by a writer whose name was Bharata. This book changed my relationship to Literature and Art. It gave me a new lens to look at the art I was consuming and engaging with on a day to day basis.

At this time I was deeply immersed in the world of theoretical frameworks to critically analyze the art I was consuming. I was pursuing a Bachelor’s Degree in English Literature and I was expected to write numerous papers where I used these theoretical frameworks to discuss and breakdown texts. The main theoretical frameworks I used to critically analyze literature included

Formalism, which focuses on structure, style, and literary devices within the text itself

Historical and Cultural Criticism, which examines how a work reflects or responds to its time and place

Marxist Theory, which analyzes literature through class struggle, power, and ideology

Feminist and Gender Theory, which explores how texts construct or challenge gender roles and identities

Psychoanalytic Criticism, which delves into the unconscious motivations of characters and authors

Structuralism and Semiotics, which interpret literature as part of larger systems of meaning

Post-Structuralism and Deconstruction, which highlight ambiguity and question stable meanings

Reader-Response Theory, which emphasizes the reader’s role in constructing meaning

Postcolonial Theory, which critiques the legacy of colonialism and the representation of race and identity

Ecocriticism, which considers the relationship between literature and the natural environment.

These frameworks provided me with some diverse lenses through which literature could be interpreted and understood. However I was soon overwhelmed because these frameworks made me engage with all Art through a critical lens. I was always looking for the politics of the artist rather than understand the emotion they were trying to convey. I was struggling and was really not enjoying the literature I was reading on a day to day basis now.

Does Art always have to have deeper meaning?

What about Art for Beauty? What about Art for Pleasure?

Can’t humans create Art to appreciate something beautiful? Art allows us to slow down, frame, and deepen our perception of beauty whether it’s found in nature, a person, an idea, or an emotion. I was echoing some of the frustrations Susan Sontag wrote about in her book titled, Against Interpretation (1964) where she stated that,

In most modern instances, interpretation amounts to the philistine refusal to leave the work of art alone. Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, conformable.

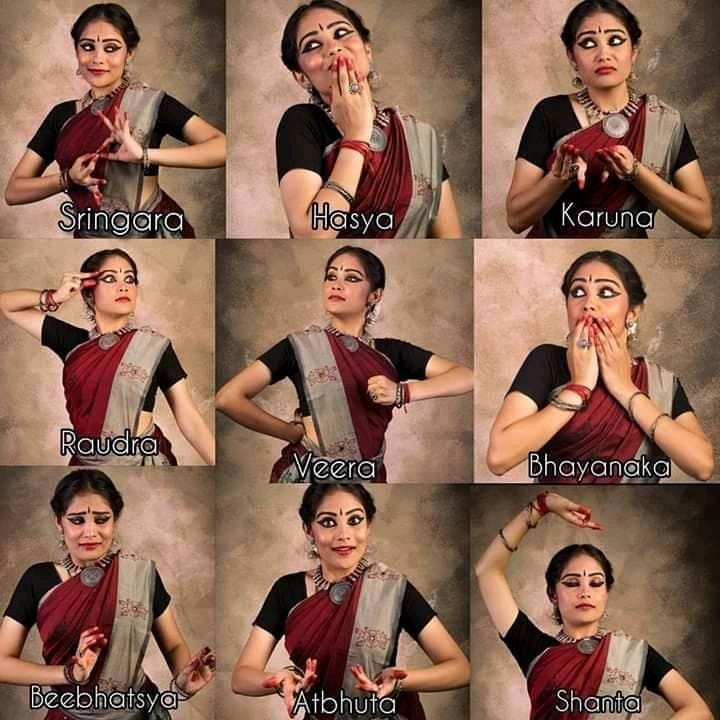

But the Nāṭya Shāstra changed things for me as a student. The Nāṭya Shāstra is a Sanskrit treatise on the performing arts. The text is attributed to Bharata, and its first complete compilation is dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE, but estimates vary between 500 BCE and 500 CE.

This is a foundational text on Indian performing arts, encompassing drama, dance, and music, and serving as a comprehensive guide for both practitioners and theorists. Composed between 200 BCE and 200 CE, it presents performance as a mirror of human experience, meant to educate, entertain, and uplift audiences.

At its core is the Rasa theory, which explains how emotional states (Bhavas) portrayed by actors evoke aesthetic sentiments (Rasas) in the viewer. The Rasa theory describes the emotional flavors evoked in the audience. There are Nine Primary Rasas or Navrasas according to this guide which include:

Shringara (Love)

Hasya (Laughter)

Karuna (Compassion)

Raudra (Anger)

Veera (Heroism)

Bhayanaka (Fear)

Bibhatsa (Disgust)

Adbhuta (Wonder)

Shanta (Peace)

The text outlines the relationship between actor and audience, asserting that the success of a performance lies in the evocation of these Rasas, which allow audiences to transcend everyday reality and experience a deeper emotional and moral truth. This was the core message of the book and this would now become one of my guiding principles for how I engaged with Art along with the many theoretical lenses I acquired from university.

Beyond aesthetics, the Natyashastra elaborates on four aspects of performance—physical movement (Angika), speech (Vachika), costume and makeup (Aharya), and internal feeling (Sattvika)—and stresses their coordinated use in conveying meaning. It also includes instructions on the construction of theatre spaces, rituals preceding performances, and the training of actors. In essence, the Natyashastra is not just a manual for the performing arts but a philosophical text that sees art as a vital tool for social cohesion, spiritual growth, and emotional refinement. This was in an era where there was no access to modern forms of Art like books, prints, films or digital media. In essence, the Natyashastra is not just a manual for the performing arts but a philosophical text that sees art in all its forms as a vital tool for social cohesion, spiritual growth, and emotional refinement.

However…

The Natyashastra is merely one text and human emotions are much more varied than the nine listed in this document. It also has a cultural element and human emotions are expressed in different ways in different cultures and in different countries. I had to factor that in as I looked at Art from my country and the rest of the world. There were similar treatises from other cultures that I needed to further explore to understand why humans create Art.

Some other treatises and books that explore performance and art theory from around the world apart from the Natyashastra (200 BCE to 200 CE) included:

Poetics (335 BCE) by Aristotle - One of the earliest surviving work on dramatic theory. According to Aristotle, Art is an imitation of life—of actions, not people. Tragedy imitates noble actions with serious consequences, aiming to represent universal truths. Tragedy should evoke pity and fear, leading to a catharsis—a purging or emotional cleansing of these emotions in the audience.

Myth, Literature and the African World (1976) by Wole Soyinka - Explores African cosmology, Yoruba mythology, and how they inform drama and performance aesthetics, including the idea of the “Ogunian” artist. The book argues for interpreting African literature through indigenous metaphysical frameworks rather than Western lenses. Soyinka critiques the Western notion of tragedy (e.g., Aristotle) for not capturing the communal, regenerative, and cyclical nature of African ritual drama.

Relational Aesthetics (1998) by Nicolas Bourriaud - Defines art as social exchange, community interaction over static object-making. Proposes that contemporary art creates social experiences and interactions rather than standalone objects. He argues that the artwork is a “meeting place” where viewers participate and co-produce meaning.

I had a long way to go to understand why humans create Art. But I now had some tools to understand Art at a personal level. These frameworks could be applied to all kinds of art. However I had still had so many questions.

What is good Art? Who decides what is good Art?

This is a video of an art auction at Christie’s in London in 2017 where Leonardo da Vinci's, Salvator Mundi created between 1499 to 1510, was sold for $450.3 million. That is around $450,000,000. This number has seven zeroes. I had to google how to write this amount in numerical form. This became the new world record for the world’s most expensive painting. Why was this painting so valuable? You have to watch this auction video and the bidding wars that unfolded. It is too much fun.

What is good art? Who decides what is good art? To answer these questions I found two videos that helped shape my perspective and gave me some important clues.

In the first video linked below, the team from Business Insider explored why modern art is so expensive. I particularly enjoyed their breakdown of a painting of a simple black square by Kazimir Malevich which was based on 20 years of simplification and development. The painting held value because of what it meant to the artist and what it meant to the people and communities that engaged with that piece of art in Russia. Here is the video description from the channel.

Modern art is expensive. From completely white canvases to simple abstract colours, these seemingly basic works can cost you millions. So what makes their price so high and how can they possibly be worth this much money?

In the second video linked below, the team from VICE news explored why the, Salvator Mundi painting was sold for $450.3 million at that auction. My favourite part of this video was the conversation between the reporter and a Brazilian artist and how they spoke about how a painting by a particular artist can increase museum or gallery visits, bring more international funding and increase cultural tourism by large numbers for a particular country. Here is the video description from the channel.

After nearly 20 minutes of nail-biting bidding on Wednesday night, Leonardo da Vinci’s painting Salvator Mundi, shattered the world record for the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction. Including fees, the 500-year-old rare masterpiece sold for $450.3 million. Some questioned the authenticity of the painting as truly Da Vinci but with a price tag that far surpassed initial estimates the concern now seems irrelevant. Before the sale, Vice News Tonight went to Christie's for a private viewing of Salvator Mundi with contemporary Brazilian artist Vik Muniz.

To be honest, I am still not really sure how to answer this question. I have more questions than answers. So I will list out all the questions that came to mind when I saw these videos.

How do artists value their work? Where do artists display their work? Who buys Art? Why do they buy Art? Why is some art worth millions while other Art is worth nothing? Why is Art from a certain country placed on a pedestal? Why are some artists richer than other artists? Why do some galleries get more visitors than other galleries? Why do major Tier 1 cities have most of the important museums and art galleries of the world? Do art critics have to go to a particular school or publish their work in a particular magazine to be recognized as important? Who gets to decide what works are displayed in a museum or an art gallery?

It is okay. On to the next question for now…

How do I access Art? Where do I see art?

This was the question I was most confident to answer. I access art through digital and physical means.

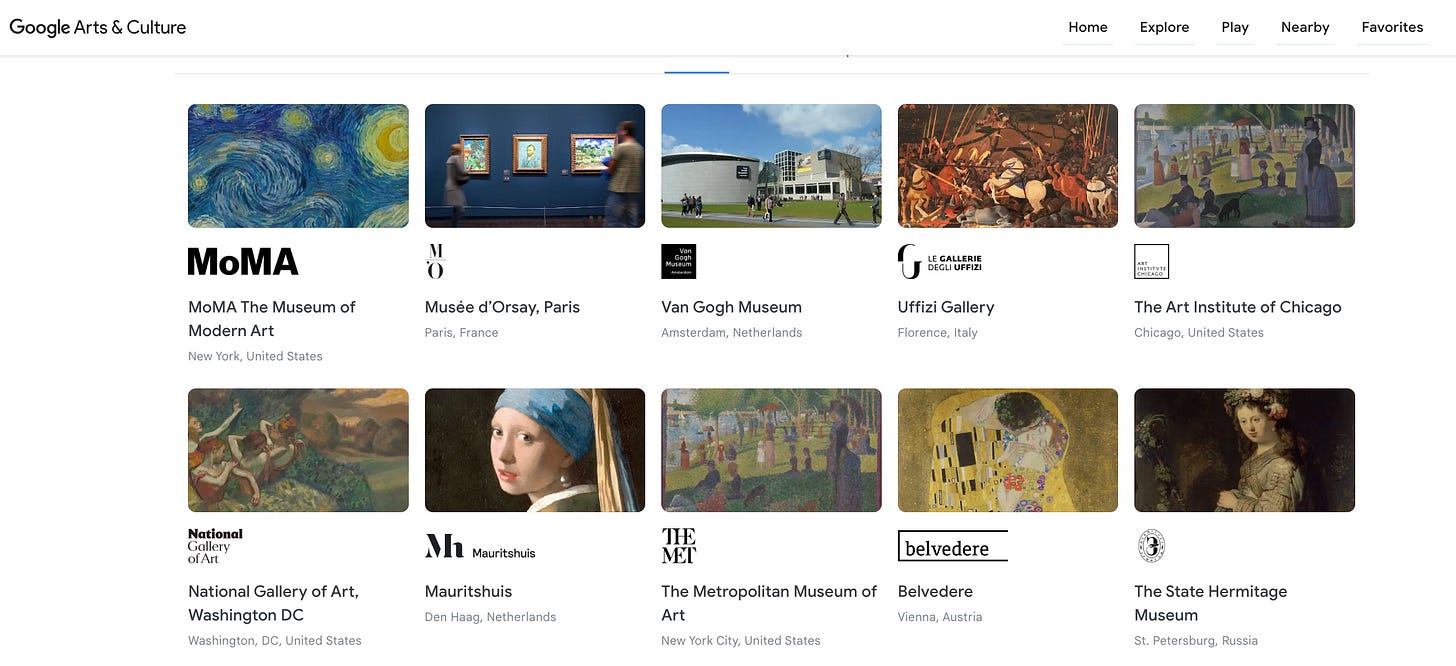

In the digital world, I access art by reviewing an artist’s website and other webpages published about them. I also access Museum Websites, Publisher Pages, Gallery Websites and digital curation sites like Google Arts and Culture. I particularly enjoy using Google Arts & Culture because it has a digital repository of art from over 2,000 cultural institutions from 80 countries. You can explore the collection through artists, mediums, art movements, historic events, historical figures and museum collections. It is my favourite weekend browsing activity. It is a lot more fun than getting lost in an Instagram Reels Blackhole. You can never escape from those. Here are some screenshots of this website and how they organize their digital archives.

In the physical world, I access art by visiting museums, art galleries, festivals and installations in my city, suburb, town or village or by doing the same in other countries around the world.

In a city like Mumbai my favourite sites to access art are the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya Museum, Prithvi Theatre, National Center for Performing Arts, NMACC, Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum, National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Jehangir Art Gallery, The DAG, The Art Loft. There are many other such spaces I have not listed here. I love visiting these spaces for new and old exhibitions and artist talks. I also enjoy participating in events like Art Night Thursday (where many galleries open their collection to the public for free for 3-4 hours) or the Kalaghoda Arts Festival (where these spaces host discussions and events with artists that live in the city). I would recommend finding a similar network in your village, city, town, suburb or district. Sometimes whatsapp groups, instagram pages and email newsletters are also great ways to find Art events you may love in the city you call home. I would love to know about such spaces in your city in the comments.

Finally…What do I want from Art?

I should be able to answer after this question after writing this extended essay and conducting this in depth personal investigation of Art.

However, I still have more questions than answers. I am happy I ended up here. I am still curious about why humans create Art. But this is what I want from Art at this point in my life.

I want Art to be my friend.

I want Art to give me comfort when my world is crumbling.

I want Art to challenge my understanding of the world I live in.

I want Art to expose me to knew ways of being that are very different from my own.

I want Art to help me become a better observer of the world around me.

I want Art to help me make sense of my many identities and the histories of the same.

I want Art to help me make sense of life and death.

I want Art to help me appreciate beauty in all its many forms.

I want Art to help me appreciate history, religion and politics.

I want Art to be a really close friend that sits with me and becomes my safe space in the good and bad times.

To end this essay, I finally decided to ask ChatGPT, why humans create Art? Here is what it had to say about this very human way of being,

Humans create art to express emotions, ideas, and identity.

Art helps us understand the world, connect with others, and leave a mark on history.

It is both a mirror of culture and a tool for imagination and change.

Until next time,

Keep making and sharing the Art you love.

Abhishek Shetty

'Economics doesn't just fund art—it helps shape what gets seen and remembered' this such a powerful line, I'm going to remember this.

I love how honestly and curiously you've explored the topic Abhishek, it shows!

Art is so many things, I personally find it very hard to summarise but when I think of it I personally feel like - Art is to strike conversation, evoke emotion, connection and tell stories.

Edward Hopper's art that you've mentioned reminded me of the book 'lonely city - Olivia Laing' have you read it? I think you might enjoy it

thank you for sharing this beautiful investigative piece, and for letting us in with such a personal lens. if art is about feeling, i felt it. also, the Tarsila reference hit home for me, but that might just be my personal bias talking.